Strategic Displacement: Russian Merchant Fleet Operations Beyond the Syrian Express

- RFN- OS

- May 11

- 4 min read

Updated: May 27

Russia has increasingly relied on its merchant fleet to discreetly transport weapons and military equipment to countries where it maintains strategic and economic interests. These unofficial maritime supply routes are frequently used to support allied regimes or conflict zones in Africa and the Middle East, often circumventing international oversight and sanctions. Civilian vessels—flagged under Russia or using flags of convenience—carry cargo destined for both state military forces and Kremlin-linked paramilitary groups such as the Wagner Group and the newer Africa Corps. This hybrid logistical model, blending commercial maritime operations with covert military supply chains, has become a critical component of Russia’s foreign strategy, enabling sustained influence and operational presence in key geopolitical theaters.

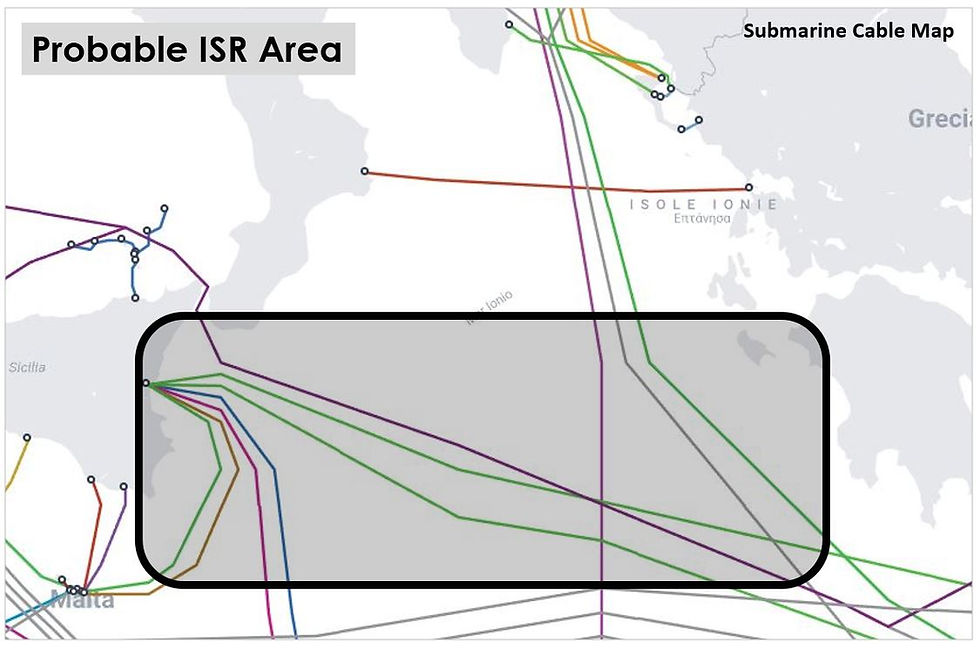

Currently, several Russian-flagged merchant vessels are operating in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, en route to ports suspected of receiving military cargo. These maritime movements suggest an ongoing logistical effort to supply matériel to partner states and Russian-aligned entities abroad. The presence of these ships in strategic sea lanes underscores the role of commercial shipping in sustaining Russia’s global military footprint, especially in regions like North Africa and the Middle East where direct military engagement is paired with covert supply operations.

Current Situation

At present, three Russian roll-on/roll-off (Ro-Ro) and cargo vessels—MV Baltic Leader, Patria, and Siyanie Severa—have departed from the port of Baltiysk in the Kaliningrad Region and have transited the English Channel, heading south. These vessels are being escorted by the Russian Navy’s Steregushchy-class corvette SKR-532 Boikiy, indicating the strategic importance of the convoy. While their exact destination remains unconfirmed, the current geopolitical context—particularly the ongoing situation in Syria—suggests that they may be bound for African or North African ports in the Mediterranean Sea, potentially to deliver military equipment or logistical support.

However, it appears that the MV Baltic Leader may have diverged from the main group, taking an alternate route. This deviation could indicate either a separate logistical objective (@RFNOSBlog).

Syria Outlook: As of the latest satellite imagery dated 2 May 2025, the port of Tartus, Russia’s key naval logistics hub in Syria, shows only containerized cargo on the quayside, with no visible military vehicles or equipment present. This suggests that there is little to no matériel currently awaiting extraction. The most recent delivery, likely conducted by the MV Sparta IV during a brief one-day stop on 26 April (@kattyfun1) - (@TiaFarris10), appears to have been minimal, indicating either a temporary pause in operations or a reduced logistical footprint at this location.

Post-Tartus Dynamics: The operational status of Russian merchant vessels previously engaged in the so-called "Syrian Express" has significantly changed in recent months—particularly following December 2024, when Russia effectively lost access to the port of Tartus due to the collapse of the Assad regime. This event marked a turning point in Russia’s eastern Mediterranean logistics, disrupting a long-standing maritime supply route for military support to Syria. Since then, the frequency and consistency of cargo ship transits to the Levant have declined sharply, with merchant vessels now rerouted or reassigned to other theaters, particularly North Africa and the Sahel region, where Russian private military contractors and strategic interests remain active.

Indicative Movements: Further confirming this potential reorientation of Russian merchant vessel operations, on 29 April, the Russian Ro-Ro cargo ship Ascalon was observed transiting the Strait of Gibraltar eastbound (@PeterFerrary) .

Initially believed to be en route to Tartus—as part of its prior role in the Syrian Express—for the recovery of remaining Russian military assets, its subsequent position north of Port Said suggests a different operational intent. The vessel now appears to be awaiting transit through the Suez Canal, indicating a likely shift toward ports in the Red Sea, East Africa, or the broader Indian Ocean region where Russia is either receiving or delivering military-related cargo. This movement aligns with a broader trend of redistributing maritime military logistics away from the Levant.

Comparable Case: A similar situation occurred a few days earlier, on 20 April, when the Russian cargo ship Maia 1 was observed transiting the Strait of Gibraltar eastbound.

The vessel remained stationary for several days, likely in anchorage or awaiting clearance, before subsequently transiting the Suez Canal. This pattern reinforces the emerging shift in Russian maritime logistics, with vessels previously associated with the Syrian corridor now potentially being redirected toward alternative strategic theaters—notably in the Red Sea, Horn of Africa, or the Indian Ocean—in line with evolving Russian military and geopolitical objectives.

In both cases, it is presumed that the cargo vessels may have conducted refuelling operations from oil tankers typically stationed in the holding area north of Port Said. If confirmed, this would illustrate a logistical modus operandi—not entirely new, but increasingly relevant—being adopted by Russia for merchant ships operating far from domestic ports, ensuring extended range and autonomy for military-support missions beyond its immediate naval infrastructure.

Regarding the Ro-Ro MAIA 1, significant research conducted by "@osc_london" suggests the vessel is involved in the transport of military material for Russia, as detailed in this report (@osc_london). The ship is currently in the Red Sea, heading south. Notably, on May 9 and 10, it followed unusual routes near Jeddah and Port Sudan—deviations that are atypical for standard commercial transit in the area. As of now, there is no OSINT evidence indicating interactions or activity involving other merchant vessels, though the irregular routing raises questions about the true purpose of the voyage and the nature of its cargo.

Conclusion:

The recent movements of Russian Ro-Ro and cargo vessels, particularly in the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal, reflect a noticeable adaptation of Russia’s maritime military logistics in response to shifting geopolitical realities—most notably the loss of Tartus and the collapse of the Assad regime. The observed patterns, including shorter port calls, escort by naval assets, and possible offshore refuelling, suggest a more flexible, decentralized, and long-range logistical model. While not entirely unprecedented, this evolution indicates that Russia is actively seeking to maintain strategic reach and support for its military and proxy operations—particularly in Africa and the Middle East—through the increased use of civilian maritime assets operating beyond traditional bases. This shift warrants continued monitoring, as it represents both a resilience mechanism and a grey-zone strategy aimed at sustaining influence under growing international constraints.

Comments